I am on vacation — and out of commission — for the next two weeks, so I wanted to use this space as a vehicle for reflection.

Since I started the Telling The Story blog last winter, I have written extensively about lessons about storytelling. Many of those have been learned through my own work as a reporter for WXIA-TV/11Alive in Atlanta. Here are three of the moments that stand out to me, along with brief snippets from the posts themselves:

Tad and Mary, and the quest to capture emotion on camera: Last April I was introduced to Tad Landau and Mary Wood. They are not famous; they are not what my producers would call “a big get” as far as stories are concerned. But they do share a beautiful friendship — and an unusual one, at that.

Landau is a firefighter for DeKalb County in Georgia. Wood is an elderly woman in his district whose 911 call two years ago was answered by Landau’s team.

The 911 call turned out to be a somewhat false alarm, but upon arriving at Wood’s house, Landau met a woman with little means or support and no living family in the area. She needed help in many ways but did not feel she could turn to anyone.

Landau changed that.

He became a friend and de facto aide for Wood, coming by her house regularly — often on shift breaks with his team — to make peanut butter sandwiches and help her sort through bills. He continues to visit faithfully and, if he does not see Wood on a given day, he hears from her on the phone.

On this surface, this was a nice story about an unique friendship. But I knew it would only work on television if I could capture that friendship organically on camera — a challenge made even steeper when I learned from Landau that Wood was very nervous about it.

But once we started rolling, it all came together.

Wood turned out to be a firecracker of a personality — an irrepressible octogenarian who quickly got used to my presence and, at least outwardly, did not worry whatsoever about being recorded. And when she saw Landau, she started glowing — no inhibitions at all.

In fact, she took advantage of my presence, making sure she said repeatedly on-camera how much she appreciated this godsend of a gift in her life.

A few days later, I attended Wood’s 90th birthday party — which Landau had organized — and again found her totally unfettered by the presence of a camera. She stole the show, and more importantly for the story, the pair allowed their friendship to shine through in a genuine fashion.

I simply did my best not to fight it. I got to know Wood by spending time with her, and I allowed both people to get comfortable with telling me their story. Then I got out of the way; in the story, I acknowledged their various on-camera winks and nods while staying in the background when those beautiful, organic moments arrived.

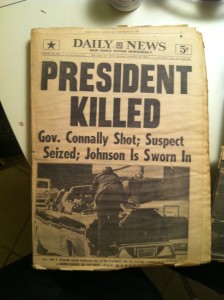

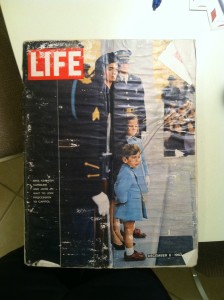

JFK, MLK, and the crafting of a civil rights documentary: I was assigned a documentary segment on the killing of John F. Kennedy, and what that meant for the civil rights movement. I went down to Dallas for a few days to get footage of the famous spots from the assassination (the book depository building, Dealey Plaza). I also interviewed several people who had been in Dallas that day, one of whom was a radio reporter at the time and stood a half-block away from Kennedy when the assassination occurred. Following that trip, I spent several days simply cobbling together old footage and photos — a difficult task, since most of the footage I wanted came with a price tag that exceeded our budget. Finally, I required two days to edit the whole thing, which included several hours reformatting all the old footage so that it looked consistent.

The process was exhaustive — and absorbing. But of all those arduous tasks, the most important thing I did was seemingly the simplest:

Listening.

In the two weeks I worked on the story, I spent a good chunk of time in conversation. I spoke with countless people in Dallas, from experts at the impressive Sixth Floor Museum to residents who lived through the era and the assassination. I reached out to other contacts, from Washington, D.C. to Atlanta, and I talked with anyone who wanted to share their memories. This included my dad, who almost immediately e-mailed me photos of the newspapers and magazines he still possessed from the days after Kennedy’s assassination.

Everybody had a story: about where they were when President Kennedy was shot; about what he meant to the modern-day Civil Rights movement; and about what that movement felt like in general — as well as what it means today.

When I first received the assignment, I knew I would need to talk with far more people than I would include in the package. I knew I would benefit as much from the unrecorded conversations than the recorded ones. And when I started having those conversations, I was continually moved with what I heard and learned.

One moment will forever stand out. In Dallas I sat down with a curator at the Sixth Floor Museum, and we discussed President Kennedy’s influence on civil rights and his reverence in the black community. We had been talking for nearly 15 minutes when she said something that floored me:

“You know, in black homes in the Sixties,” she said, “people would put up photos of JFK next to Martin Luther King and Jesus.”

I had never heard this, and I was stunned.

I followed up about it, first with the curator and then with nearly every other person with whom I spoke. Everybody I spoke with confirmed it, and one person — Fort Worth Star-Telegram columnist Bob Ray Sanders, who was in high school in ’63 — even said it on-camera.

I put Sanders’ sound bite in the final product.

And when we screened the documentary for local leaders in Atlanta, that line drew giant laughter — the kind of knowing laughter that comes with five decades of nostalgia.

The Emily Bowman story, and finding honesty amidst heartbreak: So often, many of us in newsrooms become seduced by storyline instead of substance. Maybe we focus on an issue “everyone is talking about” rather than an issue that affects people far more directly. Maybe we choose a story we can sell in one line rather than a story that needs more explanation but has a stronger payoff.

And sometimes, with stories that deal with more emotional topics, we opt for simplicity and easy-to-grasp emotions over difficult, conflicted feelings, and shades of gray.

The more I researched Emily Bowman, the more I knew I would be returning with a story far heavier than what my producers may have originally intended. I watched previous stories about Emily and learned doctors had cut out a large chunk of the teenager’s skull to alleviate swelling. I looked into the driver who hit her and found a newspaper column written by his former roommate, who defined the young man in more human terms but made his actions in this case no less unforgivable.

When I arrived at the Bowman household, I saw even more gray. Friends and family had indeed arrived to welcome Emily home, but they did so with heavy hearts for her situation and concern for her future. And yes, a local foundation had remodeled Emily’s home with a great deal of community help, but no one could say for sure whether Emily would even be aware of all the changes.

Her aunt, Suzie Mullins, summed it up: “I just hope she realizes what’s going on.”

I had never seen a homecoming quite like this, with such a pall amidst the eagerness. Beyond that, I began to feel uncomfortable with my own presence at the event, mainly because I was one of six media outlets covering it. Each of the four Atlanta TV stations sent a crew to the Bowman household, as did the local Patch.com site and a weekly paper. And we all had cameras: both the photographers shooting the event and the reporters snapping photos for their Twitter accounts. Here we stood, in the midst of a terrifying situation facing this young woman and her family, feasting on their emotions.

In that moment, I felt my own combination of emotions: empathy for the family and friends involved, sorrow for Bowman herself, and guilt — partly for simply being there, and partly for ever assuming this story might fit into a neat, obvious narrative.

Above all, I felt an increased obligation to tell the story the right way.

Matt Pearl is the author of the Telling the Story blog and podcast. Leave a comment below or e-mail Matt at matt@tellingthestoryblog.com.