Rarely, as a local TV news reporter, do I get to spend two weeks on one story.

Rarely does that story get to be eight minutes long.

And rarely do those eight minutes contain an arsenal of powerful interviews from iconic figures.

So, when I received the opportunity to work on such a story earlier this month, I knew it would be special.

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and the “I Have a Dream” speech from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. With that anniversary comes a documentary from my station in Atlanta, WXIA-TV, called “50 Years of Change”, which looks back on not just the famous march but the other major civil rights events of 1963:

- the declaration, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” from Alabama governor George Wallace

- the child protests in Birmingham

- the nationally televised speech on civil rights from President Kennedy

- the murder of Medgar Evers a day later

- the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham

- the assassination of President Kennedy

It’s an impressive list. (Last week we screened the documentary for local Atlanta leaders, and roughly three-quarters of the way through, one of the attendees turned around in his chair and remarked, “Man, a lot happened in ’63!”)

I was assigned the final story on the above list: the killing of John F. Kennedy, and what that meant for the civil rights movement. I went down to Dallas for a few days to get footage of the famous spots from the assassination (the book depository building, Dealey Plaza). I also interviewed several people who had been in Dallas that day, one of whom was a radio reporter at the time and stood a half-block away from Kennedy when the assassination occurred. Following that trip, I spent several days simply cobbling together old footage and photos — a difficult task, since most of the footage I wanted came with a price tag that exceeded our budget. Finally, I required two days to edit the whole thing, which included several hours reformatting all the old footage so that it looked consistent.

The process was exhaustive — and absorbing. But of all those arduous tasks, the most important thing I did was seemingly the simplest:

Listening.

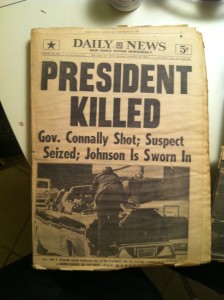

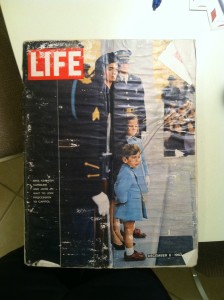

In the two weeks I worked on the story, I spent a good chunk of time in conversation. I spoke with countless people in Dallas, from experts at the impressive Sixth Floor Museum to residents who lived through the era and the assassination. I reached out to other contacts, from Washington, D.C. to Atlanta, and I talked with anyone who wanted to share their memories. This included my dad, who almost immediately e-mailed me photos of the newspapers and magazines he still possessed from the days after Kennedy’s assassination.

Everybody had a story: about where they were when President Kennedy was shot; about what he meant to the modern-day Civil Rights movement; and about what that movement felt like in general — as well as what it means today.

When I first received the assignment, I knew I would need to talk with far more people than I would include in the package. I knew I would benefit as much from the unrecorded conversations than the recorded ones. And when I started having those conversations, I was continually moved with what I heard and learned.

One moment will forever stand out. In Dallas I sat down with a curator at the Sixth Floor Museum, and we discussed President Kennedy’s influence on civil rights and his reverence in the black community. We had been talking for nearly 15 minutes when she said something that floored me:

“You know, in black homes in the Sixties,” she said, “people would put up photos of JFK next to Martin Luther King and Jesus.”

I had never heard this, and I was stunned.

I followed up about it, first with the curator and then with nearly every other person with whom I spoke. Everybody I spoke with confirmed it, and one person — Fort Worth Star-Telegram columnist Bob Ray Sanders, who was in high school in ’63 — even said it on-camera.

I put Sanders’ sound bite in the final product.

And when we screened the documentary for local leaders in Atlanta, that line drew giant laughter — the kind of knowing laughter that comes with five decades of nostalgia.

Speaking of nostalgia, I was reminded of this great bit of journalism advice I first read more than a decade ago, from Rick Reilly in the Best American Sports Writing anthology’s 2002 edition:

Sports Illustrated‘s Gary Smith, the I.M. Pei of profilers, has a rule. He’s not done researching a subject until he’s interviewed at least fifty people. That’s why he only does four a year. And that’s also why those four are often the most unforgettable of the year. They are meticulous in their depth of reporting, nearly preposterous.

I often try to channel my inner Gary Smith with producing long-form stories, but I especially kept the 50-person rule in mind on this one. I was stepping into an era about which so many people feel so many different emotions; I knew I needed to collect as many perspectives as possible before I started writing, even if I used a fraction of those perspectives in the actual piece.

I am extremely proud of how the piece turned out. And when I saw the hour-long documentary as a whole — of which my JFK segment is a small part — I again felt proud, this time to be a part of such an impacting product.

I already look back on this project, and those two weeks producing it, as a high point in my career.

(Click on the video link at the top of the page to watch the segment itself, and go to our “Share the Journey” page to watch the documentary in its entirety.)

====

FOLLOW THE TELLING THE STORY BLOG ON TWITTER!

SUBSCRIBE TO THE TELLING THE STORY PODCAST ON ITUNES!

====

Matt Pearl is the author of the Telling the Story blog and podcast. Feel free to comment below or e-mail Matt at matt@tellingthestoryblog.com.

8 thoughts on “JFK, MLK, and the crafting of a Civil Rights documentary”