The following was originally posted in 2013, when Evan Gattis was a rookie with the Atlanta Braves. This week, with the Houston Astros, he became a World Series champion.

Snooze.

I awoke to the sound of muffled radio static on the hotel room’s alarm clock. I had not bothered to find a station before I went to sleep the previous night; I was exhausted, and I doubted I would miss much by scanning the AM dial for the finest station in Abilene, Texas. I also knew I would not be listening for very long when I awoke.

Instead, I did the first thing I could think of: reach over and hit the button on top.

Snooze.

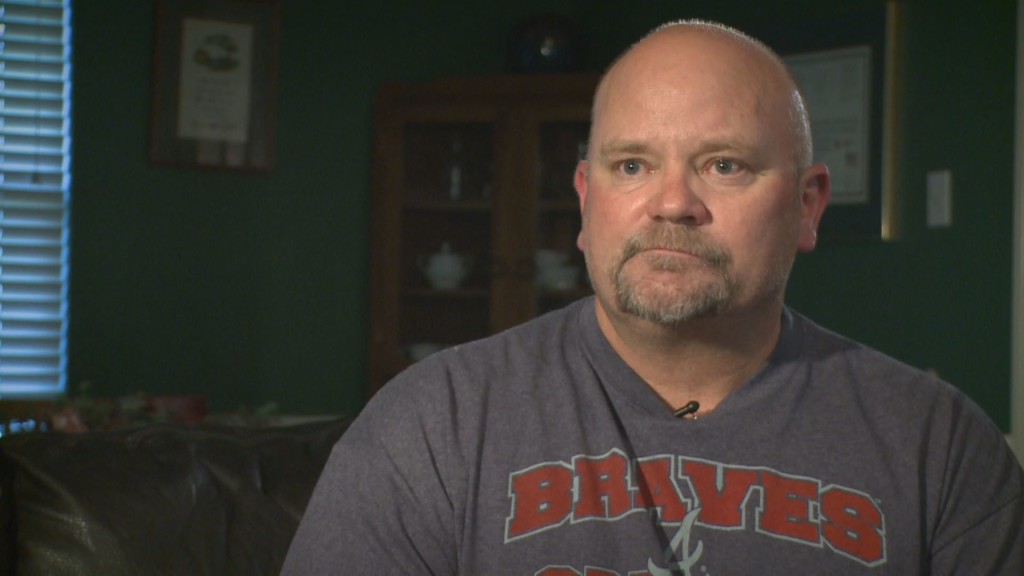

I didn’t intend to go back to sleep. I couldn’t. I was up for a reason: to drive ten hours, in one day, to interview two people, both of whom were integral to the life of Atlanta Braves catcher Evan Gattis. A month earlier, Gattis made the Braves’ Opening Day roster as a 26-year-old rookie. Two weeks after that, he was named National League Rookie of the Month.

But that was not what sent me to Texas. I had arrived in America’s second-largest state to shine the spotlight on Gattis’ other claim to fame, the story that had captivated Braves fans in Atlanta and baseball fans across the country. After completing high school and committing to Texas A&M as a highly-touted prospect, Gattis left the game and did not return for half a decade. In the meantime, he traveled the state and the country, working odd jobs at golf courses, ski resorts, and even Yellowstone National Park. He followed a spiritual advisor to New Mexico, and he lived like a nomad, on a search for purpose and identity. Gattis went on a journey, to be sure, and came out of it a Major League baseball player.

How fitting, then, that I would need to take my own journey to properly tell his story.

I got out of bed in that Abilene hotel room and took a shower. Then I heard that muffled AM static. I walked over and looked at the radio clock, flashing a time I generally only saw in the afternoon.

4:44.

I wanted to hit Snooze again. But not this time. It was time to hit the road.

*****

A day earlier I had awoken at technically the exact same time. In this case I had gotten up at 5:44, but I was still on the Eastern Time Zone, at my apartment in Atlanta preparing to leave for the airport. This in itself felt like a big step. My trip to Texas was the culmination of roughly a month’s worth of planning – and nearly an equal amount of frustration – with Gattis’ story.

The news managers at my TV station, Atlanta NBC affiliate WXIA, had decided back in April they wanted me to do an in-depth story about Gattis. It was a no-brainer, really; they had heard about Gattis’ improbable journey, watched his hot start for the Braves, and believed his story would be great for our big ratings period in May. I reached out to the Braves’ media relations team multiple times but did not hear back; I finally decided to meet Gattis myself, heading to the clubhouse for post-game interviews and introducing myself to the slugger at his locker. I told him we wanted to tell his story and even head to Texas to talk with his dad Jo, who played a huge role in Gattis’ growth both personally and professionally. Gattis gave the OK and simply asked that we go through the Braves’ media relations folks to reach his father.

Done, I said.

Over the next few weeks I sent roughly a dozen e-mails to the Braves’ PR person assigned to these types of requests. I found I could not even secure an interview with Gattis, let alone his dad. The Braves were only home for a week in late April, and numerous national media outlets had come knocking with a similar request to interview the catcher, who by this point had developed a Jack Bauer/Chuck Norris-like mystique among the team’s fans. I would have to wait until their next homestand, I was told. And what of Gattis’ dad? I heard very little.

Finally, my managers and I got tired of waiting. We wanted to tell Gattis’ story, and we no longer wanted to delay until the Braves’ media folks got around to us. “Head down to Dallas,” I was told. “Set up whatever interviews you can, and we’ll make it work.”

I spent last Monday and Tuesday making calls and developing contacts with people who had watched Gattis grow. I called his youth coach in Dallas and his college coach in Odessa; they jumped at the chance to talk about someone for whom they held great admiration. I connected with the Texas-based scout who recommended Gattis to the Braves; I got a hold of the machine shop owner who briefly hired Gattis during his time away from the game.

I even found his spiritual advisor in New Mexico. She declined my request.

I purposely abstained at this point from reaching out to Gattis’ father. The Braves’ PR person said he was expecting a call from Jo Gattis to discuss a potential interview. I was told I would hear back Monday, but by Tuesday night I still had heard nothing. By that point I had learned Jo Gattis’ phone number, but I decided I would wait until Wednesday to call him.

At that point, of course, I would be in Texas.

I gave my managers the update, and they gave me the go-ahead for Dallas. I always feel a slight trepidation when I click the “Book” button on a flight for work; it means a large financial commitment to a story, and in this case I had no idea what my trip would unearth. In baseball terms, I hoped for a home run but feared I would strike out.

No matter. Wednesday morning I awoke at 5:44, drove to Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, and hopped on a flight to Dallas-Fort Worth. I prepared to spend the next two days criss-crossing Texas, the metaphorical baseball bat gripped nervously in my hands.

*****

Dallas is a mess.

I had only spent a few hours in the belt-buckled city, but I found myself marveling in the amount of highway space per square mile. In Atlanta, another metropolis known for its sprawl, we have a particularly congested spot called Spaghetti Junction. Highways intersect and layer on top of each other. Cars move in every direction, at best like a symphony and at worst like a lurching batch of lemmings.

Anyway, I had already counted six Spaghetti Junctions in metro Dallas.

But I was off to a good start on my story. I had picked up my rental car, stopped at Chipotle for a two-burrito lunch, and headed to Coppell Middle School West, home of the Dallas Tigers youth travel baseball program. Gattis spent much of his childhood with the Tigers, a program that has churned out several Major Leaguers, Dodgers ace Clayton Kershaw and Tigers outfielder Austin Jackson among them.

I was greeted first by the weather. I had prepared for a slight chance of thunderstorms; I arrived to a combination of ominous clouds and swirling winds, which tossed my normally straight hair to the point that my head looked like Spaghetti Junction.

The gentlemen awaiting my arrival were, of course, not fazed.

“Texas in the springtime,” shrugged Gerald Turner.

Turner has been around baseball since before cable television. He coached for 30 years, then became a scout for the Royals; now he covers most of Texas and Oklahoma for the Braves. He is credited with alerting them to Gattis. Joining Turner at the park was Tommy Hernandez, who has coached the Dallas Tigers since the team’s inception two decades ago.

Both men are baseball lifers, and the game fits their personalities. Baseball folks are usually the most even-keeled guys in the room. Chalk it up to years of three-hour games, 162-game seasons, and everything else about baseball that makes it the perfect game for a patient soul. Over the course of a typical season, players and coaches receive thousands of chances to do something of impact; they gain nothing by overreacting to each one.

(Related Evan Gattis story: Early on after returning to the sport, he stepped up to the plate for his college team with runners in scoring position. He struck out. Gattis then walked over to his coach and apologized. The coach looked at him in disbelief and said, “What for?” Gattis responded, “Because I struck out with guys in scoring position.” At that point, the coach put his arm around Gattis and chuckled. “You will get plenty of chances with runners in scoring position,” the coach said. “Don’t worry about this one.”)

After chatting briefly off-camera, I put a microphone on Hernandez and set up for our interview. Then came the rain, suddenly and ferociously, forcing us to pause the proceedings while I covered my gear. We chatted some more, and when the topic turned to Gattis, both Turner and Hernandez spoke frankly about the young man who had gone through such difficulty off the field.

“He called me one time,” Hernandez recalled. “I asked him, ‘Evan, where are you?’ He said, ‘I’m working at a ski resort in Colorado.’ And I just shrugged and said, ‘OK!’”

Gattis took a slew of odd jobs after leaving the game of baseball after high school. He worked as a janitor in Dallas and a machine operator in nearby Garland. He became a golf cart boy, then a parking valet, then a restaurant worker at Yellowstone.

Through it all, the people in Gattis’ life always supported him but rarely hounded him. They did not press him about why he was doing all this or when, if ever, he would return to baseball. They all believed Gattis would ultimately find his way.

Once the rain stopped and the interview began, Hernandez remained candid in explaining exactly why he had such confidence in Gattis. “There’s a lot more to Evan than what everyone knows about or is reading about,” he said. “I think everybody assumes, ‘Oh, he’s not a good kid because he was drinking.’ He’s not a druggie or an alcoholic or a bad kid … he’s a great kid!

“He found himself in a situation that a kid his age couldn’t control,” Hernandez said. “Now, thank God he has a second chance … because a lot of kids don’t.”

And did Gattis appreciate his second chance? Turner chimed in with a story that answered that question loud and clear.

“Evan was drafted in the 23rd round (by the Braves),” Turner recalled. “I called him and congratulated him, and we had dinner. We filled out all the paperwork, signed the contract, and he got up out of the chair. He reached out to shake my hand, and he had tears coming out of both sides of his eyes.”

A poignant moment. Turner, of course, the baseball lifer that he is, couldn’t resist concluding the story with a little joke.

“I went to shake his hand, but I had my ring on, so he crushed my hand. I wanted to cry right along with him.”

*****

“I’d like to book a room for the night.”

Several hours after interviewing Hernandez and Turner, I was back at the Coppell West field, trying to make a hotel reservation from the driver’s seat of my rented Chevy Sonic. I had already driven for nearly two hours that afternoon, making stops at the aforementioned mechanics shop and golf course before popping back to the field to get footage of Tigers practice. Now I was preparing for the big drive: five hours from Dallas to Odessa, Texas, where Gattis returned to baseball after his time away from the game.

At least, I thought I was heading to Odessa.

But when I made my request to the operator at the hotel, she responded as follows:

“All right, sir. A room with one king-size bed is $309 a night.”

I quickly checked the number to make sure I hadn’t accidentally dialed the Holiday Inn in midtown Manhattan.

Nope, this was Odessa.

“What was that number again?” I asked.

“Three-oh-nine,” the operator responded, seemingly genuinely unaware of why anyone would be surprised by this.

Hernandez was not surprised. “Yeah, Odessa is big with oil guys. You can’t get a hotel room there for less than $300 a night.”

I had to re-route. Unfortunately, the nearest city on my way to Odessa was Abilene, which sported a variety of two-star hotels off Interstate-20 but would also leave me 2 ½ hours from Odessa.

I did the mental math in my head. Suddenly I was facing a potential nine hours of driving the next day – on top of the three hours ahead of me on this day.

What could I do? I rolled with it.

I think all journalists, but particularly TV reporters, are imbued early on with the spirit of doing one’s job by any means necessary. We cram an absurd number of responsibilities into a workday but never question it, and we force ourselves to make every deadline no matter how ominous the circumstances. We do not spend a whole lot of time pitying ourselves – at least not until after the fact – because we cannot afford to do so in the moment. We have no time to spare.

I especially feel this as a do-it-all journalist. I shoot and edit my own stories, meaning I take these types of road trips by myself. I need to pick up the phone if I want to complain to anything other than the air.

I do not like to complain, anyway. Beyond that, I rarely take kindly to the idea that I might not achieve the task to which I have committed.

So I booked a hotel in Abilene and hit the road, driving through steady showers in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and then darkness as I headed further down I-20. I pulled into my hotel at 10 PM, figured out how much time I would need in the morning to make my 9 AM interview in Odessa, and then grimly set my alarm for the 4 AM hour.

“That’s one advantage to being out here alone,” I thought to myself as I laid myself down to sleep. “I doubt I could convince someone else to wake up at 4:30 in the morning in the middle of Texas just for one crazy story.”

*****

Christopher Columbus never had the benefit of Google Maps on an iPhone.

But Christopher Columbus never had to find Jal, New Mexico.

The sun had barely peeked over the horizon behind me when I exited I-20, with two hours of driving already under my day’s belt, and aimed the steering wheel towards the one-lane highways that would take me to my next destination.

I was hoping to swing by New Mexico on my way to Odessa. Gattis had journeyed through the state several years earlier to follow a spiritual advisor, and while I could not interview the advisor, I figured I could probably use a “Welcome to New Mexico” sign in my story. That morning I scoured the map for the most direct route to the Texas/New Mexico border, and I found it.

All I had to do? Follow the signs to Jal.

As of the 2010 census, the city of Jal was the home of 2,047 people, its name actually an acronym for the initials of a cattle owner from the late 19th century. I knew none of that until I searched Wikipedia several days later. At this point, I simply knew I needed to head in that direction to get my shots.

In my job I have gotten used to the concept of making long drives by myself, but I never felt more alone than I did on this particular drive. I did not just lack a companion in the passenger seat; I barely saw anyone else on the highway. I did not feel lonely, by any means, but I definitely felt alone.

Something happens, though, when you are alone. You start to pay attention to details you would not notice if distracted by other people. You see the beauty in gradual change, such as when the green trees of Dallas give way to the parched plants of west Texas. You appreciate the seemingly routine, like when the sun makes its first appearance in your rearview mirror and shines a glistening golden tint on the landscape in front of you. In short, you receive a momentary glimpse of all the things on which you normally miss out – the things that make the earth a pretty special place.

As I headed toward the border, I could not help but wonder if Gattis had reached similar revelations during his numerous drives. I would later receive an up-close look at the Dodge Dakota in which Gattis toured the western side of the country. The odometer showed more than 167,000 miles. Surely Gattis spent many of those miles alone with his thoughts, pondering his lot in life, trying to make sense of the yearning and unfulfilled desires that consumed his mind.

Maybe those drives provided some clarity. Or maybe, like the sunrise, they only offered a brief taste of beauty before the responsibilities of the day – and of life – took over.

I was not about to miss my opportunity. I pulled over in my far less road-tested Chevy Sonic, popped a fresh memory card in my camera, and captured the beautiful colors of the sunrise. As I did this, a pick-up truck pulled up behind my car. An older man with burnt skin and a handlebar mustache emerged from the truck, a genteel smile on his face.

“You got a flat tire?” he asked.

“No, no,” I laughed, and pointed to the camera. He laughed back, apologized, and headed on his way.

I smiled to myself as he left. Nope, I thought, I definitely don’t feel lonely out here.

*****

“First thing’s first,” I said to the head baseball coach at the University of Texas-Permian Basin. “Where can I find your restroom?”

I had just arrived at the Odessa-based school, fresh off my brief but triumphant appearance at the New Mexico border. Since a brief 5:15 AM stop at a 7-Eleven, I had not exited the car for longer than five minutes. I was ready for the next step.

In this case, that meant an informative, enlightening interview with a man who received a front-row seat to the transformation of Evan Gattis.

Brian Reinke has coached at a variety of junior colleges and small schools in the heartland. He did not know what to expect when Gattis came into his field of vision.

“Basically,” Reinke said about his first meeting with the then-23-year-old, “I wanted to know if mentally he was in the right spot.”

By the time he arrived in Odessa, Gattis had spent five years away from baseball, feeling no desire to return to the sport. But something had happened. Something, or someone, had convinced Gattis he no longer needed to search for a deeper purpose or reason. The young man had either found what he was looking for, or, as Reinke put it, “he didn’t find something, but he realized he didn’t need to keep looking.”

Whatever the case, Gattis decided he wanted to give baseball one last chance. He came to UT-Permian Basin to play with his stepbrother, Drew Kendrick, a pitcher at the school. Reinke invited Gattis to join the team, but according to the coach, early on Gattis still felt a healthy dose of uncertainty.

“He had trouble the first couple of weeks just trying to get into a rhythm of doing everything,” Reinke recalled. “He said, ‘I don’t know if I can do this.’ All the structure put on him in high school, the expectations put on him … I think he was nervous about letting other people down.”

The slugger quickly put his fears – and anyone else’s – to rest. Gattis dominated the Heartland Conference that season, leading UT-Permian Basin in batting and hitting 12 home runs (the rest of the team combined for 19).

Beyond that, Reinke said, “he became the center of our team. He became the guy that everybody rallied around.”

Reinke recounted a moment early in the year when Gattis saw his coach fall off a ladder and break several ribs. Before practice the next day, Gattis took a rope and made a police-style chalk outline of Reinke’s body around where he had landed.

“It was hilarious,” Reinke said. He still laughs today about it, recalling how the younger men on the team were stunned that any player would have the audacity to make fun of his coach. “But, come on,” Reinke said. “What was I supposed to do?”

In less than 24 hours in Texas, I had already heard a number of stories about Gattis the Prankster and Gattis the Superhuman Athlete. But I also heard an equal number of stories about Gattis the Great Human Being. A day earlier at the Dallas Tigers’ field, Tommy Hernandez spoke of how Gattis still practices with the Tigers’ current crop of players whenever he comes home.

On this day in Odessa, Reinke very quickly followed the chalk outline anecdote with a second story. He talked about how, when his wife was very sick recently, Gattis regularly called to check in and provide support.

And, Reinke said, Gattis still calls to this day. “He will send a video to my son,” said the coach. “He will talk to my wife on the phone. He is that kind of person that you absolutely love and want to see him do the best that he can.”

Reinke then added, “He has done more with his one opportunity that I think he ever could have dreamed.”

*****

Ten hours of driving. Zero minutes of music.

These were my stats as I zoomed along I-20 on a 360-mile journey from Odessa back to Dallas. Somewhere in the 3 PM hour, I hit double digits in driving hours for the trip, and I had not yet listened to a single song.

I love music, of course, but I probably love it too much for a trip like this. I am an unabashed sing-along-in-the-car guy, and I will rock out in the driver’s seat under the right conditions.

But rocking out requires energy. I needed to conserve mine.

I decided early in the trip to take a page from the baseball lifers and remain even-keeled throughout. I already did not plan on getting much sleep, and if I fed off adrenaline, I reasoned, I would eventually crash hard at an inopportune moment. I needed to be on top of my game, from Wednesday’s touchdown at Dallas-Fort Worth to Friday’s departure back to Atlanta.

So, instead of bobbing my head to my favorite songs, I listened to podcasts. Instead of gulping down drinks with caffeine, I sipped on bottled water and green tea. And when I felt the occasional dip in appetite or energy, I sucked a few Tic-Tacs.

Quite the life, this road-tripping business.

I thought back to my off-camera conversation with Hernandez and Gerald Turner. We talked about Turner’s job as a scout for the Braves, and I asked him about his work schedule.

“From January to now,” Turner said, “I have maybe had six days off.”

“And those were probably days it rained,” Hernandez joked.

I posited that Turner probably tries to do whatever he can during these months to keep a semblance of normalcy and routine. Turner quickly shook his head.

“There’s nothing you can do, man,” he said. “You’re traveling all over the place, you don’t know what the weather’s gonna be, and you don’t know when you might have to turn around and drive all the way across the state.”

A day later, Turner’s answer still surprised me. I could not imagine going months at a time without any kind of structure. I thought of the discipline required to live a semi-nomadic lifestyle while still maintaining one’s health and sanity. I also wondered if the opposite was true: perhaps someone like Turner thrives off of unpredictability and lack of structure. After all, he spends his life trying to predict the future, scouting high school and college athletes for a Major League Baseball team. Maybe that lifestyle has seduced him, in a way.

Maybe it had a similar effect on Gattis. Maybe he felt nervous upon arriving at UT-Permian Basin because he was suddenly returning to a more structured world. Maybe, even today, he appreciated the opportunity in those five difficult years away from the game. Maybe those years – and those 167,000 miles – provided Gattis the path to where he is today.

I, on the other hand, was starting to drag. I had now been in Texas for more than 24 hours, and I was starting to feel my eyelids getting a little heavy. I knew I would probably be fine for the remainder of the trip, but I could already imagine the exhaustion I would feel this weekend upon returning to Atlanta. That exhaustion was starting to creep into my drive.

And then I checked my voice mail.

*****

“Good afternoon, Matt. Jo Gattis here.”

The voice on the message belonged to Evan Gattis’ father.

“Hope your trip to Odessa went well … some good people out there. I don’t know if we’re still on for tonight or not, but I hope we are.”

I had actually spoken with Jo Gattis a day earlier. When I had arrived at the Tigers’ field, Tommy Hernandez immediately called him up and gave me the phone.

I heard, on the other end of the line, a man who could not have sounded more excited to speak about his son.

I was excited, too, and remained so upon hearing Gattis’ latest message. I still had so many questions about his son’s history and mindset, and I believed he could provide some of the answers. I also did not yet know whether I would get to interview the player himself, so I had to treat his father as my best window into Gattis’ head.

I drove several more hours, all along I-20, somehow avoiding whatever traffic I had expected as I reached Dallas at rush hour. I headed 30 miles past the big city to the far smaller city of Forney, which the Gattis family calls home.

(Forney, as of the latest census, sports a population of nearly 15,000. Thus, while it is much smaller than Dallas, it is seven times the size of Jal, New Mexico.)

I exited the Interstate, made a few turns, and headed to what would be the most revealing interview of the trip.

*****

Less than two minutes after I turned on the camera, Jo Gattis was in tears.

I had asked him a simple question: What has this experience felt like for you?

“You really don’t expect that somebody is going to get (to the Major Leagues),” he responded, “let alone someone you know, or one of your kids, so …”

And then he choked up.

“It’s great,” he spurted a few seconds later, cutting his words short in order to secure the levees around his eyes.

Much like everyone else I met in Texas, Jo Gattis held nothing back. For the next twenty minutes, he spoke candidly about pretty much everything involving his son.

On whether Evan liked baseball as a kid: “He didn’t want to play. He cried. I said, ‘I’m signing you up to Tee-ball.’ And he went, ‘Waaaaah!’”

On Evan’s potential when he was younger: ““He got to be eight years old, and I had parents saying, ‘Your son throws the ball too hard. Tell him not to throw the ball too hard!’ I said, ‘You need to teach your son how to catch!’”

The candidness continued when Gattis talked about his son’s tougher times, starting with his initial decision to turn away from baseball when he had initially committed to playing at Texas A&M.

“His mother put him in rehab, and he agreed to it,” Gattis said, “Evidently he was just smoking some pot and drinking. Sixty days later, they said, ‘Hey, your son doesn’t have a drug problem. He has other issues, but he’s not a drug addict.’”

The elder Gattis said everyone gradually realized the bigger issues.

“The fear of failing is what got him,” he said. “He was afraid of being on the big stage, and getting caught for smoking pot, like he’s probably the only student at A&M at 17 that (would be) smoking pot. He was like, ‘I don’t want to go down there and fail a drug test, and then everybody would say this great baseball player was just a dope-head.’”

When his son started to tour the country seeking solutions, Jo Gattis rarely tried to intervene. He, like everyone else, always had faith that Evan would find his way, and he always provided whatever emotional support his son required. He recalled just one instance where he tried to set Evan straight, and it fell flat.

“I decided to have that talk on the porch,” Gattis said. “I told him, ‘You’re selling yourself short. You’re a good baseball player.’ He looked at me and said, ‘I am never playing baseball again.’”

The elder Gattis paused for a few seconds, letting the statement sink in for me as much as it did for him.

“What are you supposed to say?” Gattis asked. “’How ‘bout them Cowboys?’”

Eventually, of course, Evan Gattis found both the spiritual answers he sought and the passion for the game he once loved. His father could not speak enough about that.

“When I do get to talk to him, he says, ‘I’m great. I love it.’ He’s having a good time. This is what he wants to do.”

And then, the elder Gattis smiled just a little wider, reflecting the pride that comes with watching your child finally figure it all out.

“He told me several times, ‘I’m gonna play baseball for a long time.’ And I believe him.”

*****

My long Texas journey ended with a pleasantly short drive.

I awoke Friday morning at 5:30 AM, hopped in the rental car, and took the side streets to Dallas-Fort Worth Airport. The total drive time? Fifteen minutes.

My total drive time for the trip? Fifteen hours.

After finishing such a surreal adventure, I found myself pleasantly surprised by the ease with which the rest of the Evan Gattis story fell into place. I interviewed Gattis himself that Saturday at Turner Field, and much like his father, he offered honest, thoughtful insights about his past and present. I wound up with a mountain of on-camera interviews, videos, and photos; more importantly, I felt I had obtained the necessary perspective to produce a story on such a complex individual.

But even after all that, I still could not help and think about the journey.

How many chances do we ever receive to be alone with our thoughts and the world? Of those chances, how many do we actually recognize and appreciate? These are the times when we simply think about things, with no hurry to arrive at the answers. These are the times when we notice the details and discovery in the world around us. These are the times when we come up with our most profound revelations.

Simply put, these are the times when we reveal our selves to ourselves.

Perhaps I should never have been surprised that someone as cerebral as Evan Gattis would find value in such a journey. His voyage took, not two days, but five years. He searched for meaning while seeing the country, and he resurfaced with the drive, determination, and conviction to become a Major League baseball player.

All these thoughts, of course, would come to me later. On this day, I dropped off the rental car, flew home to Atlanta, and at long last plopped my head on my own pillow, ready to take part in an activity I had done so sparingly in the past few days.

Snooze.